Another important characteristic of Latin verbs besides their tense, person, and mood is their voice. There are only two voices - active and passive. There are also some funky verbs called "deponent verbs," but let's talk about active and passive first.

ACTIVE AND PASSIVE IN ENGLISH

Active verbs are verbs where the subject is doing the action. This is just the normal, everyday version that you are most likely seeing when you first learn the verb. Examples of this would be:

I teach you see

they punched we were watching

Notice that an active verb can be any person (I, you, he, we, y'all, they) and it can be any tense (present, perfect, imperfect, etc.) and still be active. The point here is that the subject is doing the action. It'll make more sense how that's important when you see the passive.

Passive verbs are verbs where the action is being done to the subject. Go back and take a second to look at the examples of active verbs I just gave you. Now look at their passive versions.

I am taught you are seen

they were punched we were being watched

See the difference? In the active "I teach," I am doing the teaching. But in the passive "I am taught," the teaching is being done to me, even though I'm still the subject of the verb. It doesn't matter what person the verb is (I, you, he, we, y'all, they) and it doesn't matter what tense (present, perfect, imperfect, etc.) - what matters is whether the subject is doing the action, or the action is being done to the subject.

Here's an example of an active sentence, then the passive version of that sentence.

Active Passive

I took the test. The test was taken by me.

Notice how in the active sentence, I am the subject, and I am doing the action. In the passive sentence, the test is now the subject of the verb, but the action is happening to the test.

I teach you see

they punched we were watching

Notice that an active verb can be any person (I, you, he, we, y'all, they) and it can be any tense (present, perfect, imperfect, etc.) and still be active. The point here is that the subject is doing the action. It'll make more sense how that's important when you see the passive.

Passive verbs are verbs where the action is being done to the subject. Go back and take a second to look at the examples of active verbs I just gave you. Now look at their passive versions.

I am taught you are seen

they were punched we were being watched

See the difference? In the active "I teach," I am doing the teaching. But in the passive "I am taught," the teaching is being done to me, even though I'm still the subject of the verb. It doesn't matter what person the verb is (I, you, he, we, y'all, they) and it doesn't matter what tense (present, perfect, imperfect, etc.) - what matters is whether the subject is doing the action, or the action is being done to the subject.

Here's an example of an active sentence, then the passive version of that sentence.

Active Passive

I took the test. The test was taken by me.

Notice how in the active sentence, I am the subject, and I am doing the action. In the passive sentence, the test is now the subject of the verb, but the action is happening to the test.

ACTIVE AND PASSIVE IN LATIN

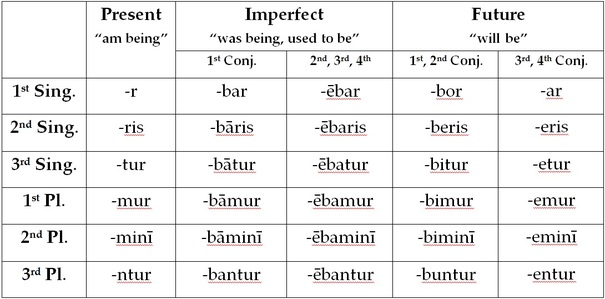

In Latin, passive verbs have their own grammar structure. The present, imperfect, and future tenses all have fairly simple and straightforward endings. All you do is take the "-re" off the infinitive and add one of the following endings:

Some of the endings do change a bit based on what conjugation the verb is, but in the imperfect tense, that just amounts to a one-vowel difference, and in the future tense, that follows right along with how future active verbs normally go, so that's not such a big deal after all.

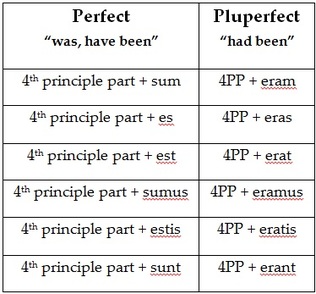

The perfect and pluperfect passive, however, are formed differently. What you do here is you take the fourth principal part, give it the appropriate personal ending, and add a version of the verb "be." Don't worry, it's not as complicated as it sounds. First, here's the chart:

The perfect and pluperfect passive, however, are formed differently. What you do here is you take the fourth principal part, give it the appropriate personal ending, and add a version of the verb "be." Don't worry, it's not as complicated as it sounds. First, here's the chart:

DEPONENT VERBS

Deponent Verbs

There are certain verbs in Latin that look passive, but act active. What that means is that they use passive endings (-r, -ris, -tur, etc.) in all their tenses, but when you translate them, their meaning is active. For example, the verb sequor means "I follow." Notice that the ending is the "r" from the first person present passive, so it LOOKS like it should mean "I am being followed," but in reality, it just means "I follow." Similarly, you'd translate "he follows" as sequitur. Looks like a passive verb, but acts active instead.

Note: deponent verbs do NOT have a passive version of themselves. They cannot be passive at all. You have to find another way to say them in an active voice. So, going back to the example of sequor, it means "I follow." Since it's deponent, there is no way of saying it in the passive voice, as in "I am being followed." Instead, you'd have to find a way to say it actively, so maybe say instead, "Someone is following me."

Deponent verbs are really obvious when you go look them up in a Latin dictionary or the glossary in the back of your book. Look at this list of verbs and see which one you think is the deponent.

ambulo, ambulare, ambulavi walk

bibo, bibere, bibi, bibitus drink

conor, conari, conatus sum try

delendo, delendere, delevi, deletus destroy

If you chose conor, conari, conatus sum, you're right! Notice that it's got the first person present passive -r ending on the first part, the passive infinitive -ari on the second part, and the third principal part is a first person perfect passive. All of these parts look passive, but they all act active - so conor means "I try," conari means "to try," and conatus sum means "I tried."

So when you're reading a passage and you come across a verb that looks passive, how do you know whether it's a deponent? Well, that's a bit annoying - you just kinda have to know the list of verbs that are deponents. It's kind of a long list, but many of them rarely ever get used, and you won't really have to worry about the rare ones. Here's a list of some of the most common deponent verbs:

Common Deponent Verbs:

arbitror, -ārī, -ātus sum to think

mereor, -ērī, meritus sum to deserve, earn

patior, patī, passus sum to suffer, permit, allow

nāscor, -ī, natus sum to be born; be found

cōnor, -ārī, -ātus sum to try, attempt

polliceor, -ērī, pollicitus sum to promise

proficīscor, proficīscī, profectus sum to set out, depart

revertor, -ī, reversus sum to go back, return

hortor, -ārī, -ātus sum to encourage, urge

videor, -ērī, vīsus sum to seem

sequor, sequī, secūtus sum to follow

orior, -īrī, ortus sum to rise, arise

moror, -ārī, -ātus sum to delay

vereor, -ērī, veritus sum to fear

ūtor, -ī, usus sum to use, make use of (+ abl.)

potior, -īrī, potītus sum to get possession of (+ abl.)

mīror, -ārī, -ātus sum to wonder at, be surprised

loquor, loquī, locūtus sum to speak, talk

morior, -ī, mortuus sum to die (fut. act. part. = moritūrus)

Also, there is at least one important case where you can learn a whole bunch of deponents by learning one concept. There are a fair number of deponent verbs that end in -gredior, -gredi, -gressus sum. These verbs all have something to do with going somewhere. For example, ingredior means "I go in," egredior means "I go out," congredior means "I meet" or "I go near," and so on. So instead of memorizing that whole list of "-gredior" verbs, just remember that "-gredior" means "I go" and then just modify it based on the prefix: "in-" means "in," "e-" means "out," "con-" means "near or with," etc.

There are certain verbs in Latin that look passive, but act active. What that means is that they use passive endings (-r, -ris, -tur, etc.) in all their tenses, but when you translate them, their meaning is active. For example, the verb sequor means "I follow." Notice that the ending is the "r" from the first person present passive, so it LOOKS like it should mean "I am being followed," but in reality, it just means "I follow." Similarly, you'd translate "he follows" as sequitur. Looks like a passive verb, but acts active instead.

Note: deponent verbs do NOT have a passive version of themselves. They cannot be passive at all. You have to find another way to say them in an active voice. So, going back to the example of sequor, it means "I follow." Since it's deponent, there is no way of saying it in the passive voice, as in "I am being followed." Instead, you'd have to find a way to say it actively, so maybe say instead, "Someone is following me."

Deponent verbs are really obvious when you go look them up in a Latin dictionary or the glossary in the back of your book. Look at this list of verbs and see which one you think is the deponent.

ambulo, ambulare, ambulavi walk

bibo, bibere, bibi, bibitus drink

conor, conari, conatus sum try

delendo, delendere, delevi, deletus destroy

If you chose conor, conari, conatus sum, you're right! Notice that it's got the first person present passive -r ending on the first part, the passive infinitive -ari on the second part, and the third principal part is a first person perfect passive. All of these parts look passive, but they all act active - so conor means "I try," conari means "to try," and conatus sum means "I tried."

So when you're reading a passage and you come across a verb that looks passive, how do you know whether it's a deponent? Well, that's a bit annoying - you just kinda have to know the list of verbs that are deponents. It's kind of a long list, but many of them rarely ever get used, and you won't really have to worry about the rare ones. Here's a list of some of the most common deponent verbs:

Common Deponent Verbs:

arbitror, -ārī, -ātus sum to think

mereor, -ērī, meritus sum to deserve, earn

patior, patī, passus sum to suffer, permit, allow

nāscor, -ī, natus sum to be born; be found

cōnor, -ārī, -ātus sum to try, attempt

polliceor, -ērī, pollicitus sum to promise

proficīscor, proficīscī, profectus sum to set out, depart

revertor, -ī, reversus sum to go back, return

hortor, -ārī, -ātus sum to encourage, urge

videor, -ērī, vīsus sum to seem

sequor, sequī, secūtus sum to follow

orior, -īrī, ortus sum to rise, arise

moror, -ārī, -ātus sum to delay

vereor, -ērī, veritus sum to fear

ūtor, -ī, usus sum to use, make use of (+ abl.)

potior, -īrī, potītus sum to get possession of (+ abl.)

mīror, -ārī, -ātus sum to wonder at, be surprised

loquor, loquī, locūtus sum to speak, talk

morior, -ī, mortuus sum to die (fut. act. part. = moritūrus)

Also, there is at least one important case where you can learn a whole bunch of deponents by learning one concept. There are a fair number of deponent verbs that end in -gredior, -gredi, -gressus sum. These verbs all have something to do with going somewhere. For example, ingredior means "I go in," egredior means "I go out," congredior means "I meet" or "I go near," and so on. So instead of memorizing that whole list of "-gredior" verbs, just remember that "-gredior" means "I go" and then just modify it based on the prefix: "in-" means "in," "e-" means "out," "con-" means "near or with," etc.